SCADA

Supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) is a control system architecture comprising computers, networked data communications and graphical user interfaces (GUI) for high-level process supervisory management, while also comprising other peripheral devices like programmable logic controllers (PLC) and discrete proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controllers to interface with process plant or machinery. The use of SCADA has been considered also for management and operations of project-driven-process in construction.

Explanation

The operator interfaces which enable monitoring and the issuing of process commands, like controller set point changes, are handled through the SCADA computer system. The subordinated operations, e.g. the real-time control logic or controller calculations, are performed by networked modules connected to the field sensors and actuators.

The SCADA concept was developed to be a universal means of remote-access to a variety of local control modules, which could be from different manufacturers and allowing access through standard automation protocols. In practice, large SCADA systems have grown to become very similar to distributed control systems in function, while using multiple means of interfacing with the plant. They can control large-scale processes that can include multiple sites, and work over large distances as well as small distance. It is one of the most commonly-used types of industrial control systems, in spite of concerns about SCADA systems being vulnerable to cyberwarfare/cyberterrorism attacks.

Control operations

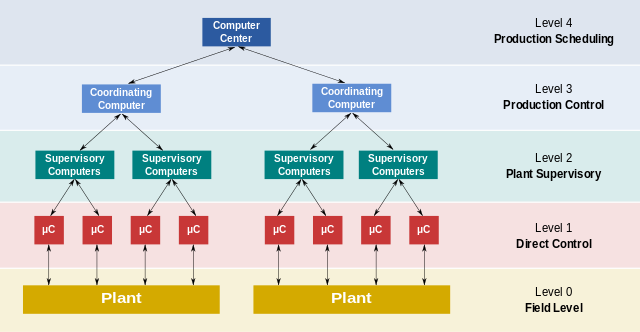

The key attribute of a SCADA system is its ability to perform a supervisory operation over a variety of other proprietary devices. The accompanying diagram is a general model which shows functional manufacturing levels using computerised control. Referring to the diagram, Level 0 contains the field devices such as flow and temperature sensors, and final control elements, such as control valves. Level 1 contains the industrialised input/output (I/O) modules, and their associated distributed electronic processors. Level 2 contains the supervisory computers, which collate information from processor nodes on the system, and provide the operator control screens. Level 3 is the production control level, which does not directly control the process, but is concerned with monitoring production and targets. Level 4 is the production scheduling level. Level 1 contains the programmable logic controllers (PLCs) or remote terminal units (RTUs). Level 2 contains the SCADA to readings and equipment status reports that are communicated to level 2 SCADA as required. Data is then compiled and formatted in such a way that a control room operator using the HMI (Human Machine Interface) can make supervisory decisions to adjust or override normal RTU (PLC) controls. Data may also be fed to a historian, often built on a commodity database management system, to allow trending and other analytical auditing. SCADA systems typically use a tag database, which contains data elements called tags or points, which relate to specific instrumentation or actuators within the process system. Data is accumulated against these unique process control equipment tag references.

Examples of use

Both large and small systems can be built using the SCADA concept. These systems can range from just tens to thousands of control loops, depending on the application. Example processes include industrial, infrastructure, and facility-based processes, as described below:

Industrial processes include manufacturing, process control, power generation, fabrication, and refining, and may run in continuous, batch, repetitive, or discrete modes.

Infrastructure processes may be public or private, and include water treatment and distribution, wastewater collection and treatment, oil and gas pipelines, electric power transmission and distribution, and wind farms.

Facility processes, including buildings, airports, ships, and space stations. They monitor and control heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems (HVAC), access, and energy consumption.

However, SCADA systems may have security vulnerabilities, so the systems should be evaluated to identify risks and solutions implemented to mitigate those risks.

System components

A SCADA system usually consists of the following main elements:

Supervisory computers

This is the core of the SCADA system, gathering data on the process and sending control commands to the field connected devices. It refers to the computer and software responsible for communicating with the field connection controllers, which are RTUs and PLCs, and includes the HMI software running on operator workstations. In smaller SCADA systems, the supervisory computer may be composed of a single PC, in which case the HMI is a part of this computer. In larger SCADA systems, the master station may include several HMIs hosted on client computers, multiple servers for data acquisition, distributed software applications, and disaster recovery sites. To increase the integrity of the system the multiple servers will often be configured in a dual-redundant or hot-standby formation providing continuous control and monitoring in the event of a server malfunction or breakdown.

Remote terminal units

Remote terminal units, also known as (RTUs), connect to sensors and actuators in the process, and are networked to the supervisory computer system. RTUs have embedded control capabilities and often conform to the IEC 61131-3 standard for programming and support automation via ladder logic, a function block diagram or a variety of other languages. Remote locations often have little or no local infrastructure so it is not uncommon to find RTUs running off a small solar power system, using radio, GSM or satellite for communications, and being ruggedised to survive from -20C to +70C or even -40C to +85C without external heating or cooling equipment.

Programmable logic controllers

Also known as PLCs, these are connected to sensors and actuators in the process, and are networked to the supervisory system. In factory automation, PLCs typically have a high speed connection to the SCADA system. In remote applications, such as a large water treatment plant, PLCs may connect directly to SCADA over a wireless link, or more commonly, utilise an RTU for the communications management. PLCs are specifically designed for control and were the founding platform for the IEC 61131-3 programming languages. For economical reasons, PLCs are often used for remote sites where there is a large I/O count, rather than utilising an RTU alone.

Communication infrastructure

This connects the supervisory computer system to the RTUs and PLCs, and may use industry standard or manufacturer proprietary protocols. Both RTU’s and PLC’s operate autonomously on the near-real time control of the process, using the last command given from the supervisory system. Failure of the communications network does not necessarily stop the plant process controls, and on resumption of communications, the operator can continue with monitoring and control. Some critical systems will have dual redundant data highways, often cabled via diverse routes.

Human-machine interface

The human-machine interface (HMI) is the operator window of the supervisory system. It presents plant information to the operating personnel graphically in the form of mimic diagrams, which are a schematic representation of the plant being controlled, and alarm and event logging pages. The HMI is linked to the SCADA supervisory computer to provide live data to drive the mimic diagrams, alarm displays and trending graphs. In many installations the HMI is the graphical user interface for the operator, collects all data from external devices, creates reports, performs alarming, sends notifications, etc.

Mimic diagrams consist of line graphics and schematic symbols to represent process elements, or may consist of digital photographs of the process equipment overlain with animated symbols.

Supervisory operation of the plant is by means of the HMI, with operators issuing commands using mouse pointers, keyboards and touch screens. For example, a symbol of a pump can show the operator that the pump is running, and a flow meter symbol can show how much fluid it is pumping through the pipe. The operator can switch the pump off from the mimic by a mouse click or screen touch. The HMI will show the flow rate of the fluid in the pipe decrease in real time.

The HMI package for a SCADA system typically includes a drawing program that the operators or system maintenance personnel use to change the way these points are represented in the interface. These representations can be as simple as an on-screen traffic light, which represents the state of an actual traffic light in the field, or as complex as a multi-projector display representing the position of all of the elevators in a skyscraper or all of the trains on a railway.

A “historian”, is a software service within the HMI which accumulates time-stamped data, events, and alarms in a database which can be queried or used to populate graphic trends in the HMI. The historian is a client that requests data from a data acquisition server.

Alarm handling

An important part of most SCADA implementations is alarm handling. The system monitors whether certain alarm conditions are satisfied, to determine when an alarm event has occurred. Once an alarm event has been detected, one or more actions are taken (such as the activation of one or more alarm indicators, and perhaps the generation of email or text messages so that management or remote SCADA operators are informed). In many cases, a SCADA operator may have to acknowledge the alarm event; this may deactivate some alarm indicators, whereas other indicators remain active until the alarm conditions are cleared.

Alarm conditions can be explicit—for example, an alarm point is a digital status point that has either the value NORMAL or ALARM that is calculated by a formula based on the values in other analogue and digital points—or implicit: the SCADA system might automatically monitor whether the value in an analogue point lies outside high and low- limit values associated with that point.

Examples of alarm indicators include a siren, a pop-up box on a screen, or a coloured or flashing area on a screen (that might act in a similar way to the “fuel tank empty” light in a car); in each case, the role of the alarm indicator is to draw the operator’s attention to the part of the system ‘in alarm’ so that appropriate action can be taken.

PLC/RTU programming

“Smart” RTUs, or standard PLCs, are capable of autonomously executing simple logic processes without involving the supervisory computer. They employ standardized control programming languages such as under, IEC 61131-3 (a suite of five programming languages including function block, ladder, structured text, sequence function charts and instruction list), is frequently used to create programs which run on these RTUs and PLCs. Unlike a procedural language like the C or FORTRAN, IEC 61131-3 has minimal training requirements by virtue of resembling historic physical control arrays. This allows SCADA system engineers to perform both the design and implementation of a program to be executed on an RTU or PLC.

A programmable automation controller (PAC) is a compact controller that combines the features and capabilities of a PC-based control system with that of a typical PLC. PACs are deployed in SCADA systems to provide RTU and PLC functions. In many electrical substation SCADA applications, “distributed RTUs” use information processors or station computers to communicate with digital protective relays, PACs, and other devices for I/O, and communicate with the SCADA master in lieu of a traditional RTU.

PLC commercial integration

Since about 1998, virtually all major PLC manufacturers have offered integrated HMI/SCADA systems, many of them using open and non-proprietary communications protocols. Numerous specialized third-party HMI/SCADA packages, offering built-in compatibility with most major PLCs, have also entered the market, allowing mechanical engineers, electrical engineers and technicians to configure HMIs themselves, without the need for a custom-made program written by a software programmer. The Remote Terminal Unit (RTU) connects to physical equipment. Typically, an RTU converts the electrical signals from the equipment to digital values. By converting and sending these electrical signals out to equipment the RTU can control equipment.

Communication infrastructure and methods

SCADA systems have traditionally used combinations of radio and direct wired connections, although SONET/SDH is also frequently used for large systems such as railways and power stations. The remote management or monitoring function of a SCADA system is often referred to as telemetry. Some users want SCADA data to travel over their pre-established corporate networks or to share the network with other applications. The legacy of the early low-bandwidth protocols remains, though.

SCADA protocols are designed to be very compact. Many are designed to send information only when the master station polls the RTU. Typical legacy SCADA protocols include Modbus RTU, RP-570, Profibus and Conitel. These communication protocols, with the exception of Modbus (Modbus has been made open by Schneider Electric), are all SCADA-vendor specific but are widely adopted and used. Standard protocols are IEC 60870-5-101 or 104, IEC 61850 and DNP3. These communication protocols are standardized and recognized by all major SCADA vendors. Many of these protocols now contain extensions to operate over TCP/IP. Although the use of conventional networking specifications, such as TCP/IP, blurs the line between traditional and industrial networking, they each fulfill fundamentally differing requirements.[4] Network simulation can be used in conjunction with SCADA simulators to perform various ‘what-if’ analyses.

With increasing security demands (such as North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) and critical infrastructure protection (CIP) in the US), there is increasing use of satellite-based communication. This has the key advantages that the infrastructure can be self-contained (not using circuits from the public telephone system), can have built-in encryption, and can be engineered to the availability and reliability required by the SCADA system operator. Earlier experiences using consumer-grade VSAT were poor. Modern carrier-class systems provide the quality of service required for SCADA.

RTUs and other automatic controller devices were developed before the advent of industry wide standards for interoperability. The result is that developers and their management created a multitude of control protocols. Among the larger vendors, there was also the incentive to create their own protocol to “lock in” their customer base. A list of automation protocols is compiled here.

An example of efforts by vendor groups to standardize automation protocols is the OPC-UA (formerly “OLE for process control” now Open Platform Communications Unified Architecture).

Architecture development

SCADA systems have evolved through four generations as follows:

First generation: “Monolithic”

Early SCADA system computing was done by large minicomputers. Common network services did not exist at the time SCADA was developed. Thus SCADA systems were independent systems with no connectivity to other systems. The communication protocols used were strictly proprietary at that time. The first-generation SCADA system redundancy was achieved using a back-up mainframe system connected to all the Remote Terminal Unit sites and was used in the event of failure of the primary mainframe system. Some first generation SCADA systems were developed as “turn key” operations that ran on minicomputers such as the PDP-11 series.

Second generation: “Distributed”

SCADA information and command processing were distributed across multiple stations which were connected through a LAN. Information was shared in near real time. Each station was responsible for a particular task, which reduced the cost as compared to First Generation SCADA. The network protocols used were still not standardized. Since these protocols were proprietary, very few people beyond the developers knew enough to determine how secure a SCADA installation was. Security of the SCADA installation was usually overlooked.

Third generation: “Networked”

Similar to a distributed architecture, any complex SCADA can be reduced to the simplest components and connected through communication protocols. In the case of a networked design, the system may be spread across more than one LAN network called a process control network (PCN) and separated geographically. Several distributed architecture SCADAs running in parallel, with a single supervisor and historian, could be considered a network architecture. This allows for a more cost-effective solution in very large scale systems.

Fourth generation: “Web-based”

The growth of the internet has led SCADA systems to implement web technologies allowing users to view data, exchange information and control processes from anywhere in the world through web SOCKET connection. The early 2000s saw the proliferation of Web SCADA systems. Web SCADA systems use internet browsers such as Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox as the graphical user interface (GUI) for the operators HMI. This simplifies the client side installation and enables users to access the system from various platforms with web browsers such as servers, personal computers, laptops, tablets and mobile phones.